Don't call me a warrior

Describing someone with an illness as a "warrior" or "hero" makes me cringe. Why is that?

Hello! I’m Leigh Kamping-Carder, and this is The Heart Dialogues, the newsletter for people born with heart conditions (and the people who love them). Every other week, I bring you a candid conversation with someone who has congenital heart disease, plus essays, links, recommendations, reader threads and other good stuff about living with a wonky heart. Join this community and ensure you don’t miss the next edition.

I was probably already in my 20s when I first heard the term “heart warrior,” and it made me cringe. I had recently transitioned from pediatric to adult cardiac care, and I started to get curious about the groups raising awareness and funds for congenital heart disease. I went to one or two fundraising events and met a bunch of “heart moms,” women whose little kids had heart defects.

They looked at me and smiled. In my flushed face and full life, they saw a promise that their little boys and girls would emerge unscathed. They called their children—people like me—“heart warriors” or “heart heroes.”

I think I understand why. A warrior is brave. A hero fights a battle to win another day. When your child is undergoing surgery after surgery, why wouldn’t you want to give her a word that conveys strength and victory?

But these words—warrior, hero, even survivor—make me feel more like a myth than a person, like my life should have the satisfying narrative arc of a Hollywood movie. They smooth the roller coaster of my experiences into a straight line, turning my ups and downs into something flat and palatable. They imply a level of put-togetherness that I don’t always feel. Does a warrior ever have an off day? Do heroes get to decide which crusades they undertake? Doesn’t “survivor” mean the bad thing is in the past?

To call me “brave” means that I must be brave, even when I’m scared. To call me “strong” means that I can never falter. To call me “a miracle” is a hell of a lot of pressure. These words say more about the person who uses them—and what they want me to be—than they help me describe my own experience.

Those first encounters with the heart moms happened about a dozen years ago. The people were lovely, but the experience made me feel like I didn’t belong. I identified more as a workaholic, a sister, a Brooklynite, an art lover—any number of things, but not a patient. I drifted away from the CHD community. In the intervening years, I’ve had more heart-related complications—nothing major so far, knock on wood—but enough to make me find my way back a couple of years ago. I suppose I’m paying more attention now to how other CHDers are like me, as opposed to how they’re different.

No one has called me a “heart warrior” to my face—yet. I don’t know what I’d say if they did. For the most part, people who find out about my heart defect and surgeries typically respond with, “Whoa, that’s crazy” (a perfectly fine response) or, “Are you OK now?” (a fair question but hard to answer).

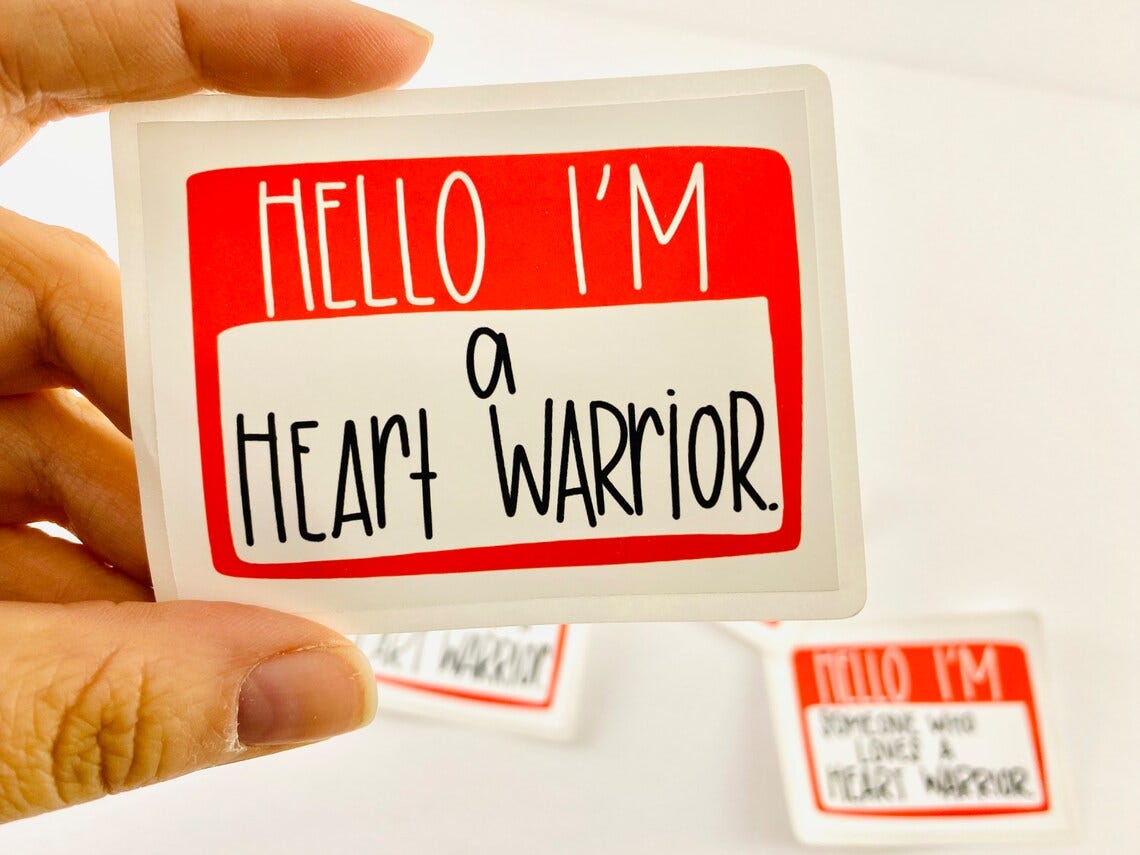

Plenty of people with congenital heart conditions use the label “heart warrior” and “heart hero.” I see those phrases constantly in articles about kids and adults with CHD, as well as splashed across T-shirts, tattoos, books, bumper stickers, onesies, fridge magnets and memes. For the record: Everyone is allowed to talk about their own bodies using the language they want. Full stop.

For some CHD folks, “heart warrior” is a badge of courage. It takes a lot to undergo a surgery or other procedure and to emerge on the other side, not having given up. To push to live another day. Some people with heart conditions do feel like they have superpowers after running a race, giving birth or getting a transplant. For many, being called a warrior is preferable to hearing, “I’m so sorry.” Pity is condescending; it’s the worst.

If I have to talk about my heart, I usually call it my bum ticker or vaguely allude to my heart stuff. In a particularly dark period a few years ago, I took to calling my heart a piece of shit or a piece of junk. I really did believe that. It had failed me again and again.

Now, I try to focus on how my heart has succeeded, pumping all these years with only one ventricle. My heart is strange and scary and frustrating and powerful, if not exactly superpowered. Giving this feeling a label would be too solemn and too simple for me. My heart is not like that.

What do you think? Do you call yourself a “heart warrior”? Why or why not?

I have, at times, called my son all of these names. Born in 1984, in Venezuela, with Shones Complex, he was in heart failure for most of his childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. He has been pacemaker-maker dependent since he was five, and he had an artificial mitral valve implanted when he was 24, which changed his life but also has made him take Coumadin every day and carefully monitor his INR. And he is the funniest, most joyful, upbeat, and sensible person I have ever met. Yes, he is a miracle, yes, he is my hero. And so are you. I understand the discomfort, of course. As my son told me, when he was 15, "you don't know what it is like to be me." No I don't, but I do understand the need to feel normal and part of the world...chd is a heavy burden, for the person with a heart defect and for the family. Yes,maybe it isn't particularly heroic to simply do what one must to live. But it is the grace that I esteem, the willingness to live and love despite the fear and the pain.

I also find the term #Warrior to be #Cringe. Maybe even a little #cheugy in the vernacular of the youth.

I'm a #MSWarrior and my son was a #HeartWarrior. They are labels I hate - along with the labels #heartmom or, shudder, #boymom. Must we cling so dearly to such stupid sounding labels?

But I used them, not often but when I did used them unironically. My son was a #heartwarrrior because it was much less depressing for me as a mom to say that to someone than it was to tell them the whole complicated and messy truth. I refer to myself as a #MSwarrior because this diagnosis and new and it feels sorta nice that there is a community of people with this disease that identify with strength. But you hit it on the nose - bravery and strength aren't optional here. Are you strong and. brave if you have no choice?