7 decades after heart surgery, a retired lawyer leads a normal life

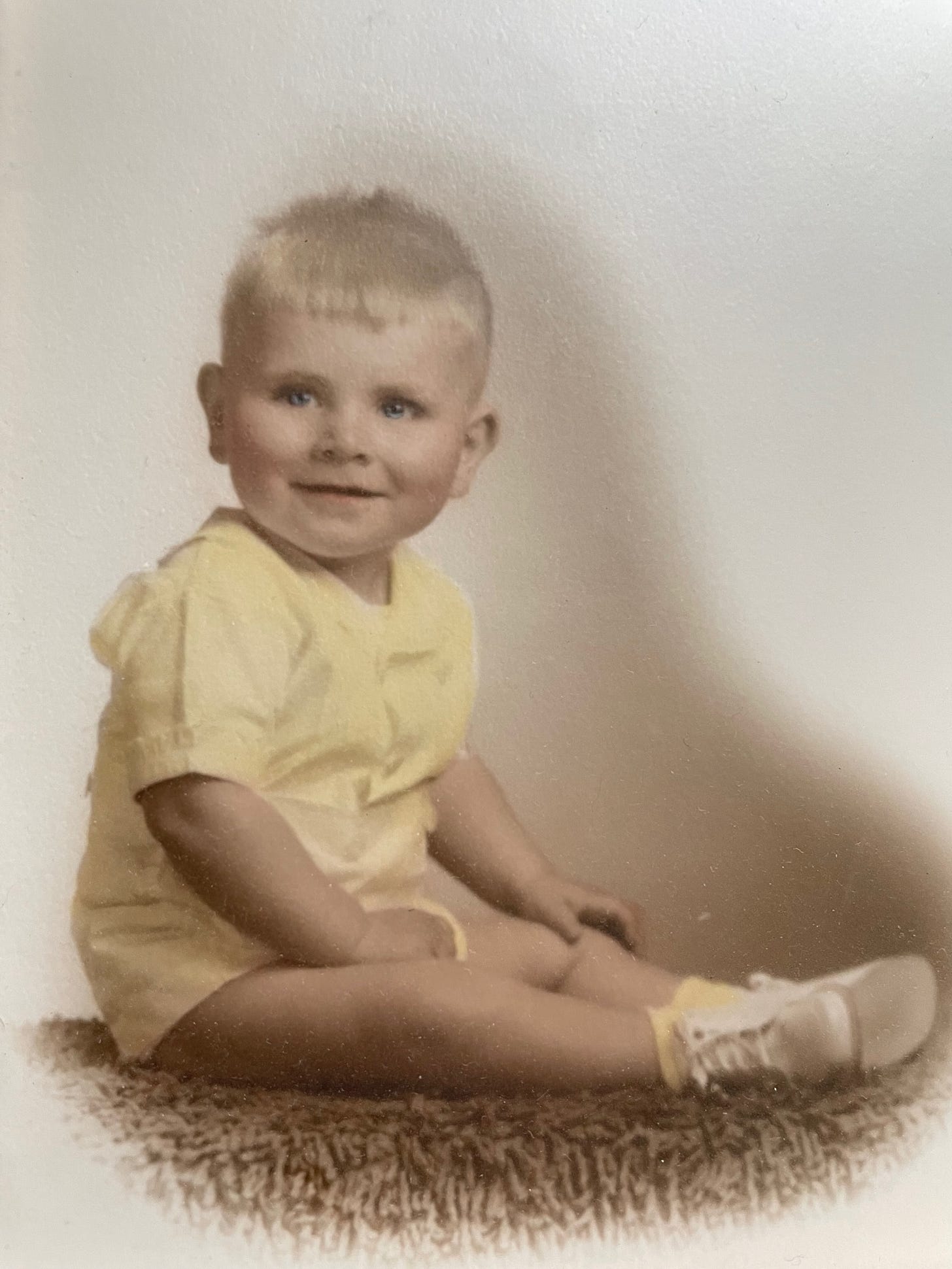

Bill Causey had an early "blue baby" operation for a congenital heart condition; getting older is "exhilarating."

Hello! I’m Leigh Kamping-Carder, and this is The Heart Dialogues, the free newsletter for people born with heart conditions (and the people who love them). Every other week, I bring you a candid conversation with someone who has congenital heart disease, plus essays, links, recommendations, reader threads and other good stuff about living with a wonky heart. Join this community and ensure you don’t miss the next edition.

Bill Causey, 74, is likely one of the longest surviving open heart surgery patients in the world. If you know something about the history of pediatric cardiology, you’ll recognize the names of his medical team: his first cardiologist, Dr. Helen Taussig, and his surgeons Dr. Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas.

Bill was born in Baltimore in 1949 with pulmonary stenosis, a narrowing of the pulmonary valve. His mother, a nurse, could tell something was wrong within days of his birth. Bill’s pediatrician sent them to Johns Hopkins, where Taussig, a pioneering pediatric cardiologist who had lost her hearing as a child, diagnosed him by listening to his heart with her fingertips, according to an account of his surgery that Bill wrote for the nonprofit Adult Congenital Heart Association. When Bill was 3 years old, Blalock performed a pulmonary-valve repair with Thomas at his side, Bill said. The trio developed the so-called blue baby operation, and they would lend their names to what is now known as the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt. (Thomas, who was Black, was not recognized for his contributions at the time.)

Read Bill’s account of his surgery and Thomas’ role here.

Bill now lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife. He retired in 2016 from a 45-year legal career, including stints at the American Red Cross and the U.S. Department of Justice, as well as teaching at Georgetown University. His decades-long interest in space led him to serve as a docent at the National Air and Space Museum for the past 20 years and to write the book, “John Houbolt: The Unsung Hero of the Apollo Moon Landings,” published in 2020. He sits on the board of directors of the ACHA.

Bill spoke with me about what he remembers from his procedure, a letter he received from Dr. Taussig and the exhilaration of getting older.

You had heart surgery when you were 3 years old. What was that like?

My mother was an Army nurse in World War II, and she could tell right away that I was having some kind of a medical problem. Because we lived in Baltimore and because she was a nurse, she found that the best thing to do was to take me to Johns Hopkins Hospital in downtown Baltimore, and have me seen by Dr. Helen Taussig, who was their chief pediatric cardiologist at the time. Dr. Taussig examined me, determined that I had pulmonary stenosis.

Over the next year or two, I continued to regress medically. I was a classic blue baby. I couldn't walk very far without having to stop and catch my breath. I had the traditional blue lips, blue fingernails. In 1952, Dr. Taussig convinced Dr. Alfred Blalock, who at that time was the chief of surgery at Hopkins, to operate on me. Initially, Blalock was reluctant to do that because I was 3 years old at the time. And he said, “Helen, I don't operate on babies anymore that young, because I found that they cannot deal with the anesthesia.” Taussig said, “Well, if you don’t operate on him, he’s going to die anyway. Why don't you give it a shot?”

She was very close with Blalock, and they worked very closely together. And Blalock said, “Okay, I'll do this.” So Blalock and Vivien Thomas operated on me in April of 1952. Unfortunately, my surgical records from Hopkins were lost in a fire in the 1960s. So I don't have my exact surgical medical file. But I have read Blalock’s two-volume papers that he wrote before he passed. What Blalock did was, he put me on a block of ice and got my heart rate down to about 40 [beats per minute]. Once he opened me up, he would have only about three or four minutes. He opened me up using the classic Blalock incision and immediately went to the pulmonary valve and opened it. Taussig immediately said, “Oh, it's clearly pulmonary stenosis. We gotta get that valve working again,” or at least working properly.

I don't know if this is true [for my operation], but I found that in later procedures, this is what Blalock did. He turned to Thomas, and he said, “Okay, put your little baby finger in that valve, and I want you to manipulate the valve for about 20 seconds, and then let's see what happens.” And apparently Thomas did that, and they looked at the valve, and the valve seemed to be now working fine. It seemed to just have to have been woken up. Blalock then said, “That looks good.” He watched it for about a minute, then he closed me up. That's apparently what the procedure was all about.

Do you remember anything from the procedure?

My very first recollection ever was when I was waking up in the hospital. This was at Easter time. I was in sort of a crib in the post-op room, and there was somebody walking around dressed up like an Easter bunny. And it scared the hell out of me. [laughs]

What was your life like after the surgery?

I attribute to my parents, and mostly my mother, who was a nurse, the fact that they wanted to have me grow up like a normal child. I knew I was a little different. People around me knew I was different. If they ever saw my scar, they could tell I had some kind of major operation. But my parents always said, “Look, you're gonna be really no different than anybody else. So you just do what you think you can. Don't think you have any limitations. And if you do have limitations, your body's gonna tell you. And you listen to your body.” I had a very normal childhood. I'd play with the kids in the neighborhood, I'd run and participate in events at school. I went on to high school, I played baseball on my high school team. I just assumed, well, I had this event when I was 3. It apparently was an important thing, but I'm like everybody else now, and I'm doing just fine.

Once a year, I'd have to go back to the hospital. I'd have a team of doctors look at me, listen to me, put a stethoscope to my chest, say, “Oh, wow. Unbelievable. Look at that.” And I'm thinking, “What in the world’s going on?” I was always told I was probably going to have a valve replacement at some point. That was always in the back of my mind growing up. But 72 years later, I haven't had a valve replacement.

Were your parents involved in your care? How did they react to your heart condition?

My mother was a nurse, so more than most mothers, she was very aware of all the medical issues that I was dealing with. And she was very careful in observing me, like any nurse would with a patient. As I now look back on it, they probably went out of their way to make sure I had a normal life and kept instilling in me the fact that I really don't have any limitations unless I felt I had a limitation. I'm an only child, and I was born several years after my parents got married. I don't know whether my condition—because it was obviously very expensive and very difficult to deal with for my parents—whether that resulted in them deciding not to have other children or not. But I think the fact that I was an only child also helped me in adapting to my condition because my parents could spend probably a little more attention on me than if they had other children. But again, they absolutely went out of their way to make sure I didn't regard myself as special or have any limitations.

In your law career, you said you’ve mostly worked as a litigator, and you’ve worked on Capitol Hill, in private practice, and for the American Red Cross, the Department of Justice’s internal affairs division and the Washington, D.C., Attorney General’s office. How did your heart condition show up at work? Were you public about it?

I didn't promote it or highlight it with people. I didn't hide it from people. A lot of people who I eventually went to work with were people who knew me for a long time, and they knew about my condition. But it never came up during work. It never became an issue. It goes back to the line I've continuously used with you this afternoon. I just made sure I had a normal life, and I was fortunately treated like a normal person by all the people I worked with. Nobody ever treated me as if I had any kind of medical limitation or heart condition. That was just fine with me.

What about in romantic relationships? How did you tell your wife about your heart condition?

We've been married for 13 years, but we've been together for about 30 years. She knew me when I was in my late 30s and early 40s. She obviously knew about my condition. I not only described it to her, but she could see that I had a condition. She could obviously see the incision and all that. She was very good about it. We didn't regard it as a handicap or an adversity or something different. It was just part of life, like other people have asthma or other people have migraine headaches. People have all kinds of illnesses and conditions, and they go on and they continue their lives. That's the way we did too. I don't think it's affected us at all.

How do you feel about your scar? Do you try to hide it?

Oh, no. As a kid I would go swimming every summer. Occasionally people would look at it and not say anything, and I would just go on my business. One of the places my wife and I have gone for over 20 years is a health resort in Arizona called Canyon Ranch. One year, I was in the men's locker room changing. I noticed that there was this guy in the locker room who was looking at me in a funny way. All kinds of things could go through your mind, but I didn't pay any attention to it. That night, my wife and I are sitting at our table in the dining room. The same guy walks over to me, and he says, “Pardon me for interrupting. I want to apologize for staring at you today in the locker room. I'm a surgeon, and I could see that you had a Blalock incision. Did you have surgery by Alfred Blalock?” I said, “In fact, yes I did.” And I could see he wanted to sit down with us at the dining table and talk about it forever. But all I said was, “Yeah, 1952, I had surgery. I'm doing fine. Thank you very much.” You ask about, am I conscious about my incision? Somebody like that will make you think about it. But I went through my entire life not thinking about it at all. And how are you doing?

I'm good. I also had quite a normal childhood. I've now interviewed a lot of people, and I will say that no matter what people have experienced—multiple surgeries, no complications—every single person says they had a normal childhood.

I think that's largely due to the fact that most of the people you've been talking with, including me, had their surgery when they were very young. What I have found in talking with people who have heart surgical procedures when they're older, they're much more affected by it. They feel that there's much more of a physical limitation on them. They’re more aware of their physical appearance. For people who have their surgeries when they're young, it just becomes a part of your life. It's not the sudden change in your life that you have when you have open heart surgery when you're 30 or 40 or 50 years old.

How did you get involved in the ACHA?

The person who really got me interested in this, frankly, was [Dr. Anitha John, an adult congenital cardiologist at Children’s National Hospital, lead investigator of the Congenital Heart Initiative, a member of ACHA’s medical advisory board and Bill’s cardiologist]. She says, “You know, there's an organization that deals with people like you who have congenital heart problems.” My initial reaction was, “Oh, that's interesting. What is it?” As I got to the point where I was going to retire and try and find new projects to work on, I talked to her more about it. She said, “Well, why don't you go on the board? Because you could certainly contribute something.” And when I contacted Mark [Roeder, president and CEO of ACHA] and other people on the board and expressed my interest, and they learned about my background and my history, I think they were quite interested and very much wanted me to join the board. I thought I could contribute to the board and to the organization. It's been quite fulfilling.

I'm going to turn 40 next year, and a lot of my friends are starting to freak out about getting older. I'm excited to get older—this is all good. I’d love to hear your thoughts on that. What do you think about aging?

The anxiety of getting older seems to hit everybody when they either turn 40 or 50. I have never seen age as an issue. Age will slow you down physically a little bit. You won't be able to do quite the number of things you could do in the past. You feel a little differently and sometimes you might get tired and so forth. But I find age to be quite exhilarating. As you get older you learn more about the diversity in the world. I don't mean that only socially, but the different places in the world, different kinds of people in the world, different things that people think about. My wife and I, we try and travel quite a bit because we do like to experience new and different places and people. So I find getting older to be, frankly, quite exhilarating. I'm not worried about it at all. We all know what the end is at some point. But I think the world is a fascinating place right now. I don't have any anxieties or frustrations at all about getting older. I find it to be just a unique challenge every day. Just enjoy it, enjoy the moment.

Is there anything else you wanted to add?

Let me close with a true story again. Back in the early ’70s when I was visiting my parents in Baltimore one day, I happened to notice a television interview with Dr. Taussig. I stopped and obviously was frozen and watched it. I was so pleased to see this interview with her. She, I think, had just retired. And I sat down and I wrote her a letter. She knew who I was because she had seen me for years and years and years. And she wrote me back a handwritten letter, and it basically was one sentence. And it said: “Dear Bill, the fact that I have received a letter from you convinces me that my life has been worthwhile.” That sort of wraps it up, right? What a moment that was when I got that letter from her. Here's someone writing me that letter who was standing in the operating room when I was 3 years old, when I was having my surgery. And what she's saying to me. It was quite a moment when I got that letter.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

What did you think of Bill’s story? Tap the button to leave a comment.

I read Bills comments with great interest. He is just a little older than I. My mother was also trained as a nurse during WW2. In my role as chair for Gift of Life NE Ohio I do many presentations for fund raisers to help us preform heart surgeries in the developing world for children born with CHD. I start every presentation with "how many of you have heard the term "blue babies" . Most have not. As I explain in the US today we just fix them. In the developing world no one knows what the issue is until the child dies. Their is no cardiac care for most of the kids in the developing world. Bills comment from Dr. Taussig's letter to him upon her retirement is the way I feel as I occasionally get the chance to reconnect with a child we helped who is now a teen or young adult. I know they will do wonderful things with their life. Makes me feel my volunteerism with this organization gives my life of value too.

That is an amazing story!❤️❤️